Written by Nicola Mountfort (Pastoral Leadership student, Eastview Baptist Church)

Pōwhiri

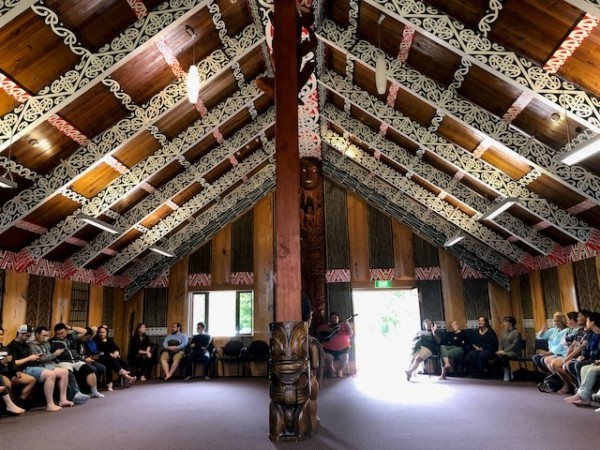

Arriving at Te Whetū-o-Te Rangi marae, we were a group of a few friends and many strangers. We were about to embark upon the pōwhiri, a process of weaving together the tangata whenua and ourselves, the manuhiri.

The kaikaranga from the marae initiated this ceremonial ‘weaving’ process.[1] She called, and our kaikaranga responded. Their voices mingled eerily and beautifully with aroha and emotion as they exchanged greetings, explained our presence and purpose, and payed respect to our ancestors.[2] We were welcomed to enter, so we slowly advanced together onto the marae, led by our kaikaranga, and sat in our assigned seats.[3]

Then began several whaikōrero, spoken in a tauutuutu pattern, alternating back and forth from hosts to visitors.[4] Like a new mat, a whāriki, being woven, stories were being entwined, slowly and patiently. Each whaikōrero was followed by a waiata, with voices woven together in complementary song.

Our koha was duly presented to the tangata whenua at the culmination of the whaikōrero, showing our gratitude at the hospitality we were about to receive. Then we threaded our way to individually and physically greet the tangata whenua with hongi, the weaving of breath, and with harirū, shaking of hands.[5]

The pōwhiri was completed with the sharing of kai together––delicious seafood chowder from the local moana. The mana of each group is recognised through the pōwhiri, and now we could relax informally together. We were no longer strangers, we were woven together as whānau.

Weaving––Raranga

This tikanga of pōwhiri was hugely impacting on me. Upon arriving at the marae I was venturing into the unknown. I was unsure of marae protocol, but wanted to behave appropriately and respectfully. What impacted me most was the metaphor of weaving. From the start of the pōwhiri people were woven together, through the call of the karanga, the tauutuutu pattern of the whaikōrero, voices woven in waiata, and the weaving of breath through hongi. Eating together wove us together even closer.

I felt welcome there. I felt at home and at peace. After the pōwhiri the weaving continued, with our stories woven together via pepeha––the sharing our whakapapa, more waiata and kai. Even the snoring overnight in the wharenui could be said to be melodies woven together, perhaps!

The literal weavings were significant too. We learned that the tukutuku panels, which line the wharenui, are woven from both sides. My small group joined the amazement of our Fijian friend when he noted that tukutuku means “communication” in Fijian. We were weaving, communicating and connecting together, in a way that bound us as one.

Artefact

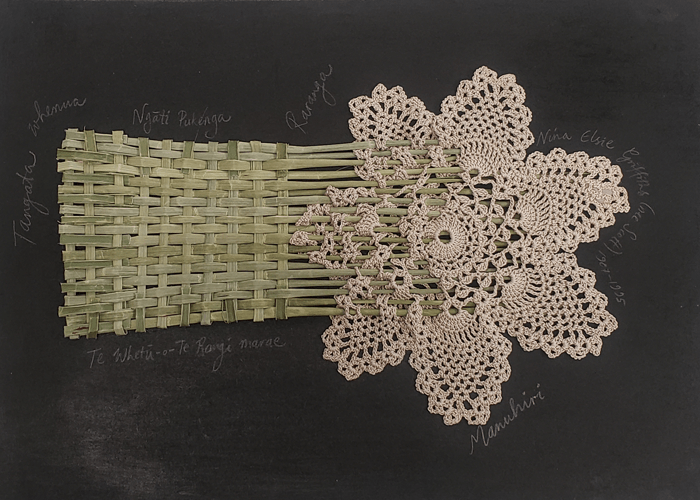

My artefact is inspired by the weaving together of people by the pōwhiri. On the left I’ve woven flax into a simple whāriki.[6] This represents the tangata whenua. On the right is a doily crocheted by my paternal grandmother, Nina Elsie Griffiths, née Scott (1907-1995), whose grandparents hailed from England and Scotland.[7] I am a fifth-generation Pākehā New Zealand woman and the doily represents me (and others) as manuhiri.[8]

I’ve woven together the two elements in the centre, and even though both the flax and the doily are woven together they continue to retain their uniqueness. They are woven together, but not assimilated.[9]

They each retain their mana––Māori will continue to be Māori, and Pākehā will continue to be Pākehā, but each can enrich the other. I believe there is great beauty where the two have been woven together, with an intricacy that requires the coming together of the two to achieve. Significantly, the flax strengthens the doily, acting like a scaffold. The tangata whenua indeed provide a strong foundation for Aotearoa.

How pōwhiri concepts might be incorporated within our worship communities

Rewai Te Kahu issued a challenge during the poroporoaki to us as church leaders. That challenge is to weave people together. The pōwhiri is a process which effectively weaves people together in a way where each retain their mana, so there are powerful concepts which churches can learn from pōwhiri.

Incorporating pōwhiri concepts in any way involves slowing down and being patient. On the marae one does not slip in, or out, unnoticed. All are welcomed with correct protocol and woven in. Noting this, perhaps our churches could consider making our welcoming processes more significant and specific? Even if this was just slightly formalised that would enable people to feel a greater sense of belonging. Simple things could help, like ensuring each arriving person is intentionally welcomed at the door. Also the corporate welcome from the front could be given more emphasis, with increased usage of multiple languages. Another possibility could be to incorporate the traditional ritual of “passing the peace,” where congregants harirū––shake hands––with everyone they can reach, enabling physical connection. Even though some people remain nervous about touching others because of Covid, when it is safe to do so the gift of touch expresses welcome and inclusion in an embodied way.

Sharing of kai is another pōwhiri tikanga which weaves people together. Food allows people to relax together. Currently in many churches we share a cup of tea together after the morning service, but regular shared lunches, for example, increase the weaving together of people.

These pōwhiri concepts of slowing down and intentionally welcoming people, and of sharing kai and stories together would allow our people to be woven together. We would increasingly come to understand, know, and appreciate each other. It would allow all peoples to retain their mana, and grow in aroha with one another. In summary, the pōwhiri process is a beautiful example of weaving people together, which our worship communities can learn much from.

Thanks so much to Manaakinui Te Kahu for coordinating this noho marae, and to Ray and Shanene Totorewa for hosting us.

[1] Suzanne Duncan and Poia Rewi, “Ritual Today: Powhiri,” in Te Kōparapara: An Introduction to the Māori Worldview. by R. Michael et al. (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2018), 127.

[2] Duncan and Rewi note that Karanga are central to the demonstration of aroha and the expression of emotion.

Duncan and Rewi, “Ritual Today: Powhiri,” 127.

[3] We sat with men in front and women behind, at a right-angle to the wharenui and the iwi who had gathered to welcome us.

[4] Duncan and Rewi, “Ritual Today: Powhiri,” 130.

[5] Duncan and Rewi, “Ritual Today: Powhiri,” 132. “The term harirū has been developed from the Western practice of enquiring as to the wellbeing of another which has resulted in it transliterated form of harirū, from ‘how-do-you-do’.”

[6] I harvested this flax from my garden, endeavouring to follow tikanga. For example I said a karakia before harvesting, was very careful which leaves to choose, and harvested in the sunny part of the day. My weaving is amateur, but I enjoyed the process. I look forward to seeing the flax lighten to a similar colour as the doily as it dries.

[7] In 1861 William Diamond and Johanna Thomson (my Nana’s maternal grandparents) arrived in Aotearoa via Sydney. In 1867 they bought land on the West bank of the Aorere River, in Collingwood. The Diamond farm remained in the family until 1929.

Jan Botica, Diamonds and Gold on the Aorere: A family story of William Diamond and Johanna Thomson of Golden Bay, New Zealand and Their Descendants, (JK Botica: Epsom, 2005), 27.

[8] I am fifth-generation on my maternal grandparents’ side: My maternal grandmother’s great-grandparents, William Parker and Harriet nee Austin arrived in Aotearoa from England on 12/12/1840. Also English, my maternal grandfather’s grandfather, George Allen arrived in 1860 on The Egmont.

[9] I am conscious to push back against the assimilationist rhetoric, such as politician Brash’s dream of forgetting the past and moving towards a utopian “single multi-ethnic NZ race,” an idyllic “melting pot” of “coffee-coloured people”, (as expressed in his “Nationhood” speech to the Orewa Rotary Club, 27 January 2004), and other contemporary manifestations of this ideology.

Mikaere, “Are We All New Zealanders Now? A Māori response to the Pakeha Quest for Indigeneity.”

Bibliography

Botica, Jan. Diamonds and Gold on the Aorere: A family story of William Diamond and Johanna Thomson of Golden Bay, New Zealand and Their Descendants. JK Botica: Epsom, 2005.

Duncan, Suzanne and Poia Rewi. “He Tātai Tuakiri: The ‘Imagined’ Criteria of Māori Identity.” Pages 372-394 in Te Kōparapara: An Introduction to the Māori Worldview. by R. Michael et al. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2018.

Duncan, Suzanne and Poia Rewi. “Ritual Today: Powhiri.” Pages 121-136 in Te Kōparapara: An Introduction to the Māori Worldview. by R. Michael et al. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2018.

Duncan, Suzanne and Poia Rewi. “Tikanga: How Not to Get Told Off!” Pages 30-47 in Te Kōparapara: An Introduction to the Māori Worldview. by R. Michael et al. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2018.

Mikaere, Ani. “Are We All New Zealanders Now? A Māori response to the Pakeha Quest for Indigeneity.” Pages 97-119 in Colonising Myths–Māori Realities: He Rukuruku Whakaaro. Wellington, Huia, 2011.

I thoroughly enjoyed this article and was educated further at the same time. Thanks, Nicola

A wonderful article , so informative and so well written!